Indonesia to Enter New Climate Chapter as Paris Agreement Is Signed

This blog was originally published in The Jakarta Post.

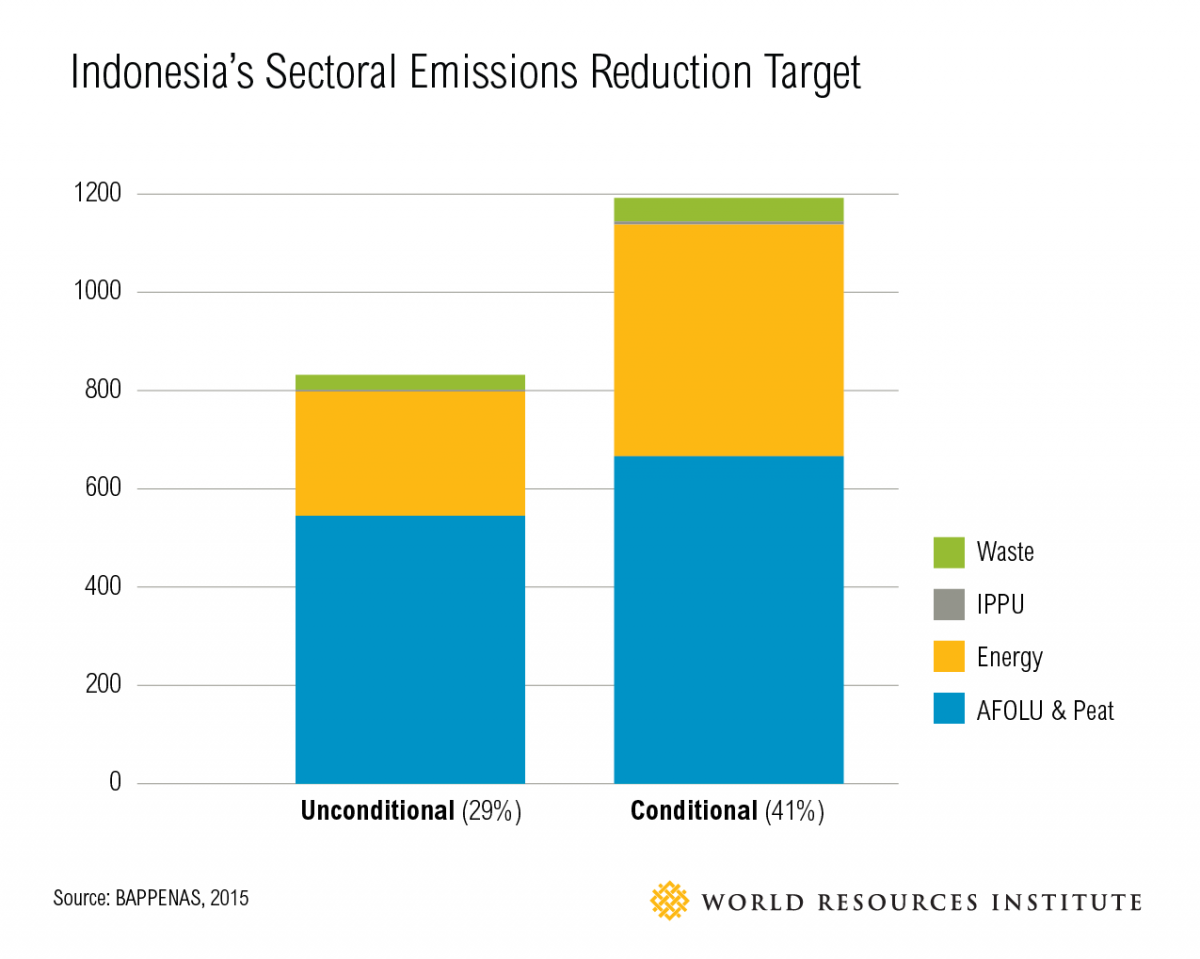

“As a country that hosts one of the largest forests in the world, Indonesia has decided to become part of the solution,” marks President Joko Widodo during his speech at COP 21 in Paris last December. ‘Becoming part of the solution’, Indonesia commits to unconditionally reduce its emissions by almost a third (29 percent) against 2030 business-as-usual (BAU) scenario or more (41 percent), provided that international assistance is available.

On April 22, the historic Paris Agreement will be signed in New York, marking the world’s sixth largest emitter to start walking the talk.

Ahead of this signing, Minister of Environment and Forestry Siti Nurbaya made an encouraging statement about how Indonesia’s NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution) should be an enhanced and more ambitious version of the climate goal submitted to UNFCCC, known as the INDC (Intended Nationally Determined Contribution). Realizing her vision of ‘guiding the nation to transform into a low-carbon development’ as a signatory to the Paris Agreement, Indonesia needs to ensure that there is strong national ownership followed by successful ratification for it to take effect.

Beyond shaking hands, it is also important to understand what achieving these climate targets entails. While recent analysis pointed out that 21 countries managed to decouple economic growth from emissions between 2000-2014, Indonesia has yet to identify when its emissions would peak, let alone the national roadmap to get there. Through the hazy horizon, however, there are four things we could be certain about regarding Indonesia’s climate action:

1. Land and Energy Sectors as the Backbone of Mitigation Efforts

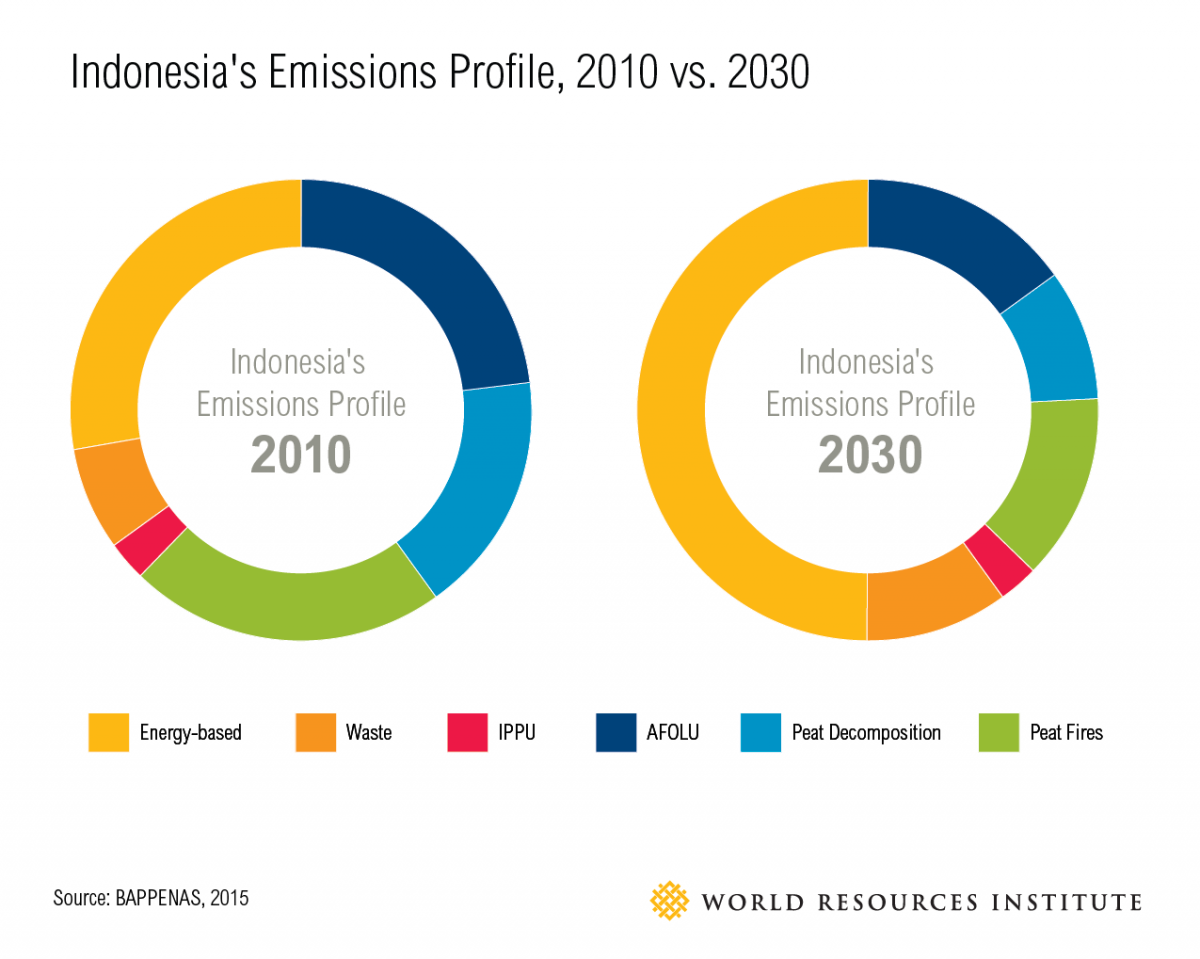

Land-based and energy-based emissions contribute up to 90 percent of Indonesia’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2010 and projected emissions in 2030 (BAPPENAS, 2015), albeit with slightly different composition (see graphics below). That said, contrary to popular belief that Indonesia should prioritize its forestry sector, safeguarding both in parallel is consequential in accomplishing the country’s climate goals.

In its INDC, Indonesia already highlights peat restoration and sustainable land use management, along with accelerated renewable energy development as its main vehicle to progress toward significant emissions cut. However, questions remain regarding what achieving these targets would look like.

2. Going Beyond Unconditional Target Requires Holistic Energy System Transformation

An analysis on Indonesia’s Sectoral Emissions Reduction Target (BAPPENAS, 2015) shows that most of the additional emissions reduction in the conditional scenario will be energy-based. Thus, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources and energy private actors may hold the aces to accomplish Indonesia’s ambitious target of 41 percent reduction against BAU scenario. The establishment of Center of Excellence for Clean Energy that seeks to accelerate and facilitate clean energy initiatives in Indonesia while greening the current electricity grid is an important milestone steering toward the right direction.

The fact that 50 million Indonesians live with limited or no access to modern energy services provides an opportunity to shift into renewable energy while addressing the urgent challenge. Albeit existing programs to nationally reach 100 percent electrification ratio—including the heavily-coal-based 35GW power plant development—are tactical in the short term, it could lock Indonesia into a high-carbon energy system in the long term.

Hence, shifting to more mini-grid and off-grid renewable energies in Indonesia’s most remote areas based on optimized energy mix modelling should be done immediately. Coupled with concrete and active demand management policies, this approach would help Indonesia achieve significant emissions reduction.

3. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s Forests Still Provide the ‘Low-Hanging Fruits’

Since a severe forest and peat fires episode hit Indonesia in 2015, the country has been under a lot of pressure to manage its land use more sustainably. Indeed, Indonesia bases 65 percent of its unconditional emissions reduction on Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) and peat management mitigation efforts, demonstrating that land-based activities still provide most of emissions reduction potential.

Previous analysis has identified that extending moratorium policy to cover not only primary forests and peatlands but also secondary forests, revoking existing undeveloped concession permits within forested area and restoring 2 million hectares of peatlands and 12.7 million hectares of unproductive lands could be some of the activities that will help Indonesia achieve its reduction target.

4. Horizontal Synergy and Vertical Coordination Are Foundational

Lastly and most importantly, President Widodo needs to put in place a good climate governance that is founded on a robust synergy between ministries in different sectors and a strong coordination with subnational governments. Since climate change is a cross-cutting issue that involves many aspects, working strictly based on mandates, tasks, and functions (Tupoksi) could pose a significant risk that will slow down Indonesia’s progress toward its climate goals.

Indonesia’s biofuel target is an instance where land-based and energy-based ministries need to work together to attain the goal without sacrificing the country’s remaining intact forests. Concurrently, subnational governments could benefit from national assistances in achieving their respective emissions reduction goals, known as RAD GRK (Rencana Aksi Daerah Penurunan Gas Rumah Kaca). Provisions of provincial climate data, in particular, could provide insights that would help national government as well as other relevant actors provide effective technical assistances and capacity building for local agencies.

While signing the Paris Agreement opens up a new climate chapter for Indonesia, understanding these four key aspects is also an indispensable step that would help Indonesia avoid future obstacles in implementing its climate plans.