Improving the Lives of Indigenous Communities through Mapping

A Case Study from Indonesia

Synopsis

Overlapping land use and tenure uncertainties are prevalent in Indonesia. The One Map Initiative at the Village Level (Inisiatif Satu Peta di Tingkat Desa; ITUPEDE) supports Indonesia’s One Map Policy to address these problems, primarily through participatory mapping. It helped the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community to map its territories and improve land-use planning based on local wisdom. It helped make land boundaries clearer and mapped more inclusively. Agreements restricting deforestation in specified areas were enacted and adequately implemented.

Key Findings

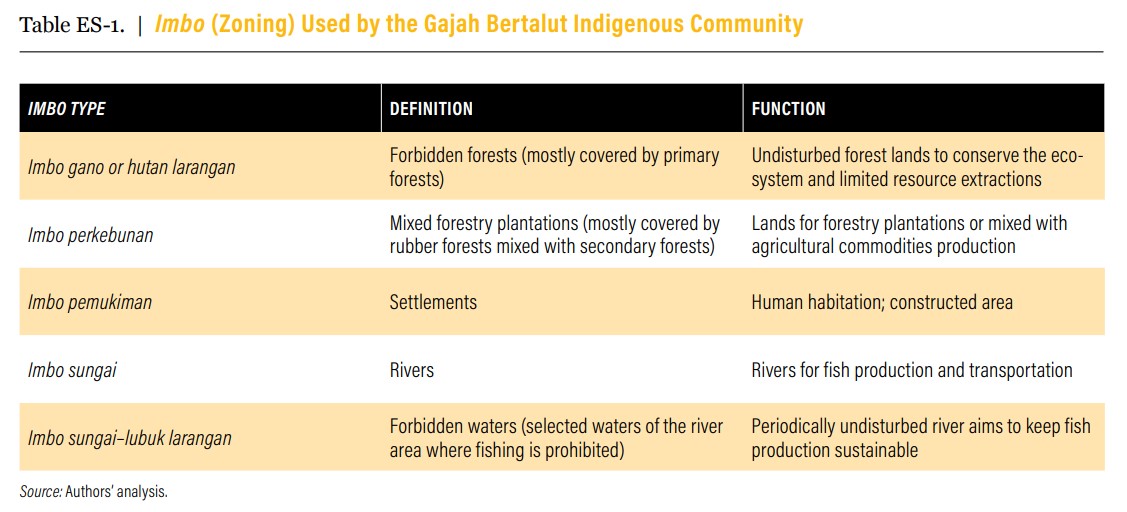

Our findings show that the traditional land management practices of the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community emphasize forest protection. Based on our field observations, we found that the community has been accused of illegal logging, which caused some government representatives to be skeptical of recognizing the community’s land rights. We investigated the community’s local wisdom regarding land management to better understand the situation. We found that, although the community does, in fact, log trees within its territory, it is guided by local wisdom that emphasizes sustainability in forest management practices and promotes elements of common property. This local wisdom is expressed by the imbo, or zoning, system (see Table).

Based on our observation, ITUPEDE helped the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community map its territories and improve land-use planning. By facilitating the communities through participatory mapping, land boundaries became more evident, and the process was partially inclusive. As shown in Map ES-2, this outcome led to community agreements that stipulated complete prohibitions on deforestation in imbo gano (forbidden forest zones) and partial prohibitions in specific new zones, such as in imbo pemanfaatan (utilization forest zones) and imbo cadangan (temporary reserved forest zones). In both of these new zones, resource extraction is allowed—including tree harvesting for noncommercial purposes—but it requires the permission of the indigenous elders. Areas considered to be imbo cadangan, in particular, are reserved for the community’s future generations.

Based on our observation, ITUPEDE helped the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community map its territories and improve land-use planning. By facilitating the communities through participatory mapping, land boundaries became more evident, and the process was partially inclusive. As shown in Map ES-2, this outcome led to community agreements that stipulated complete prohibitions on deforestation in imbo gano (forbidden forest zones) and partial prohibitions in specific new zones, such as in imbo pemanfaatan (utilization forest zones) and imbo cadangan (temporary reserved forest zones). In both of these new zones, resource extraction is allowed—including tree harvesting for noncommercial purposes—but it requires the permission of the indigenous elders. Areas considered to be imbo cadangan, in particular, are reserved for the community’s future generations.

We found that the community had consistently restricted deforestation per its local wisdom from 2001 to 2020, based on analysis of tree cover loss data and Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) alerts from Global Forest Watch’s data set. This finding reveals that local wisdom has reliably guided forest protection in the area long before ITUPEDE. Figure ES-1 shows the tree cover loss trend in different zones of Gajah Bertalut. In 2001–19, tree cover loss primarily occurred in imbo perkebunan (mixed forestry plantations). This zone had 10 loss alerts detected in 2020, which are still classified as “probable loss.” The relatively more restricted zones, such as forbidden forests, temporary reserved forests, and utilization forests, experienced less to no tree cover loss. The ITUPEDE team validated that the loss in forbidden forests in 2015–16 was caused by forest wildfires, not by the community.

Our findings indicate that, with the spatial evidence collected through ITUPEDE, the community improved its negotiations for land rights recognition. The district government became more receptive to the community and rescinded previous decisions that had limited the community’s rights, particularly by issuing a regent decree in late 2018 that recognized the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community and its lands. Therefore, we believe that the materials produced through the ITUPEDE process, such as maps, served as an entry point to establish a common language between stakeholders, to begin indigenous forest recognition by the government, and to strengthen the implementation of the One Map Policy.

We found that the community requires further negotiation to address legal constraints over indigenous forest rights. Despite the district government’s recognition, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry stated that the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community would need to be recognized under PERDA before the indigenous forest could be legitimized. Such legislation is politically challenging because it requires the local parliament’s approval.

Executive Summary

- Overlapping land use and tenure uncertainties are prevalent in Indonesia. This situation has created adverse consequences for environmental protection as well as the negotiating power of indigenous communities over land rights. The establishment of the Rimbang Baling Wildlife Reserve partly on land settled by the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community reflects this problem—and the country’s chronically poor forest and land governance system.

- The One Map Initiative at the Village Level (Inisiatif Satu Peta di Tingkat Desa; ITUPEDE) supports Indonesia’s One Map Policy to address the land governance problems, primarily through participatory mapping.

- ITUPEDE helped the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community to map its territories and improve land-use planning based on local wisdom. It helped make land boundaries clearer and mapped more inclusively. Agreements restricting deforestation in specified areas were enacted and adequately implemented.

- The spatial evidence and documentation collected by ITUPEDE increased the subnational government’s acceptance of the Gajah Bertalut indigenous community, which led it to rescind its earlier decisions limiting the community’s rights. However, for the national government to officially recognize the community, a local regulation (peraturan daerah; PERDA) must first be issued by the local parliament.

Projects

One Map Initiative at the Local Level/Inisiatif Satu Peta di Tingkat Tapak

Visit ProjectOne Map Initiative at the Local Level is a collaborative initiative to achieve a sustainable and equitable land use and planning in order to support the government to implement low-emission development.

Part of Forests & Land Use